Everywhere, monopolies and despair

It’s June 8, 2022. Here’s the rundown:

Monopolies at work

The solution to the “deaths of despair” problem in the U.S.

Numbers, links, and faces

Gas, formula, and shipping — monopolies at work

Blame cartels and monopolies for some of the financial pressures we’re all feeling.

It would be cool if President Biden could, say, wave a magic wand and lower gas prices. Or make more baby formula. Or sort out supply chains. But he can’t. No one can — and unfortunately, no quick, easy, solution to smothering inflation, either.

While we’re all feeling the crunch from shortages and price increases, it’s important to get some insight as to why this is happening: Cartels and monopolies. Essentially, many products that we depend on (like gasoline) are produced by a small number of firms or nations, giving them a stranglehold on the market.

You know the names: OPEC, Abbott, etc. You could even argue that the internet service provider market is subject to the same issue. But let’s look at a few of the big problems we’re experiencing in the U.S. right now.

Gas prices

The average price for a gallon of gas as of 6/8 is just under $5. It’s much more expensive than we’re used to (although I’d argue, and have, that maybe it should be more expensive — don’t throw things at me). But what’s the issue? To quote this recent explainer from The Washington Post, “everything.” But in short, demand is up, production is down, and there’s a war in Europe causing further problems.

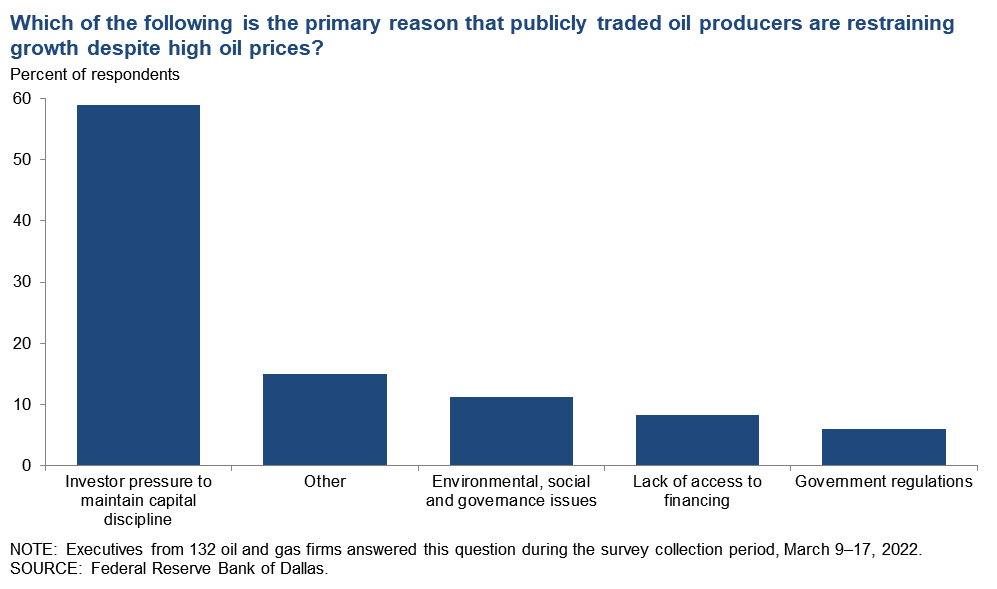

If you really want to get down to it, though, it’s mostly an issue with producers who don’t want to produce. Because, as you may have guessed, lower production means higher prices, and higher profits. Check this out, from the Dallas Fed, which surveys energy companies:

“Investor pressure” is the main culprit. To cut to the chase, the pandemic hit, demand for oil cratered, and we never really restarted production. Barring the president nationalizing the energy sector, there isn’t really much anyone can do about it — except blame the handful of energy companies (and cartels like OPEC) for keeping production low.

Baby Formula

There’s also a shortage of baby formula in this country. Somehow, despite all of our resources, we can’t feed our babies — if that’s not a failure of the highest order, I don’t know what is.

This is likewise a story of monopolistic power. While the FDA did shut down a formula plant in Michigan (which didn’t help, obviously, but was apparently needed as the place was “egregiously unsanitary”), that plant is reopening. But that goes to show that the shutdown of one production facility threw the entire market into chaos.

From a recent NPR story:

The infant formula industry is a multi-billion dollar business dominated by a handful of firms. In the U.S., just four companies control about 90% of the market, including Abbott Nutrition — the firm behind the shuttered Michigan plant.

These companies operate a relatively small number of formula factories in order to maximize efficiency and keep their production costs low.

"They're concentrating production into a few, very large plants but that creates a lot of risk," says Claire Kelloway of the Open Markets Institute, an anti-monopoly think tank. "A huge part of the crisis we're seeing now is from the closure of one plant."

Further, the U.S. has 17.5% tariffs on imported baby formula. Who does that benefit, besides the domestic baby formula monopolists? There are other regulatory barriers too, which make it difficult to buy formula from other countries.

Again, we’re at the mercy of a handful of entrenched interests.

Shipping

Finally, shipping — or, you know, supply chain stuff. Shipping companies — the ones that operate those giant container ships that carry goods all over the world — are also organized into a cartel, with outsized market power.

According to FreightWaves with data from The White House, “the top 10 ocean carriers control 80% of the industry. Nine of them are further organized into three alliances. In 2021, they earned $150 billion in profits.” So, 80% of the industry is really controlled by three main interests. That gives them a lot of control over when and where goods end up, which can have significant market effects. And it screws up supply chains.

Related reading: Giant container ships are ruining everything

And, like with gasoline or baby formula, there isn’t much we can do to spur innovation or competition in the space. These are all, by and large, “natural” monopolies, or close to them — I’m not going to go out and start a competing ocean carrier company, for instance.

But this is also sort of the natural endgame for most markets. Some firms beat out the others, killing them off or eventually absorbing them until there are only one or two big players left. Coke and Pepsi. Verizon and AT&T. And so on.

This is all to say that there’s no easy way to dial back prices. Gas prices will go back down at some point. Formula will be back on shelves, too. But it’s important to understand that a lot of the price shocks we’re witnessing are due to our reluctance to efficiently play referee in the markets, by ensuring they don’t turn into monopolistic nightmares. Of course, how much of a role a referee should play in the markets is certainly open for debate, because one blown call can upend things further.

The U.S. has a real problem with “deaths of despair,” and fixing it will take some real effort

Suicides, drug-related deaths, and more are rising. Fixing it will require some concerted effort from all of us.

Image: U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee

The U.S. experiences more “deaths of despair” relative to other countries. This includes suicides, drug overdoses, deaths as a result of obesity and alcoholism, and other horrible things.

This has been known for a while, and may not come as a surprise to some people. I, personally, have had friends succumb to suicide, drug use, and more, as many of you. A study published in February finds that Americans are dying younger — and it’s mostly among white people who do not have a college degree. This is in contrast to a control group of 16 other wealthy countries, including Canada, Australia, Japan, and some nations in Europe.

And it’s largely due to these deaths of despair. Obviously, there’s a lot that goes into that, but suffice it to say that people in our communities are having a very difficult time. There are likely a whole lot of reasons for that, including a flimsy and altogether insufficient social safety net, the hollowing-out of the middle class with many jobs having been lost to cheaper parts of the world over the past few decades, drug manufacturers purposefully and shamelessly causing drug epidemics, and the fact that many people straight up can’t afford to go see a doctor or to buy medication that they’re prescribed.

That’s all conjecture on my part, but I think it’s at least partially accurate.

Here’s the key takeaway from the study (here’s more about it from Penn):

It has been observed that human beings are constrained by evolutionary strategy (ie, huge brain, prolonged physical and emotional dependence, education beyond adolescence for professional skills, and extended adult learning) to require communal support at all stages of the life cycle. Without support, difficulties accumulate until there seems to be no way forward. The 16 wealthy nations provide communal assistance at every stage, thus facilitating diverse paths forward and protecting individuals and families from despair. The US could solve its health crisis by adopting the best practices of the 16-nation control group.

So, according to this study, we need communal support, and we need it desperately. The study concludes with this: “Without support, difficulties accumulate until there seems to be no way forward.”

Yikes.

As for what communal support entails? Probably a slew of things, like a functional and accessible health care system, serious attempts at helping feed and house people in need, mental health facilities, and so on. Not easy, not cheap. And in this country, probably not remotely doable.

I think what it comes down to, for many people, is that they’re alone, broke, broken, and run out of options. Again, I don’t know for sure, but if you’ve spent some time on the road traveling around the country at all, you’re bound to visit places that are…rough. They’re often, but not always, in rural areas. The people are desperate, proud, and may be unwilling to accept any help even if it was offered.

It’s a tough nut to crack. We’re disengaged, disinterested, and are experiencing the monetization and commercialization of nearly every small aspect of our lives, and very, very few people are benefiting from that process.

There’s a lot to unpack here, and it’s easy to make armchair-quarterback assumptions or guesses about the root of the problem, or how to fix it. But we should all know that we have a very serious problem in the U.S., and that we should be looking for ways to reach out and help if at all possible.

Similarly, another recent study I came across found that there are some stark differences in mortality rates depending on where you live, and how people in that area vote. Not to delve too far into the political sphere here (we all get enough of that anyway, don’t we?) but here’s what the study said:

Between 2001 and 2019, mortality rates decreased by 22% in Democratic counties (from 850 to 664 per 100,000), but by only half that (11%) in Republican counties (from 867 to 771 per 100,000). Consequently, the gap in mortality rates between Republican and Democratic counties jumped by 541%, from 16.7 per 100,000 in 2001 to 107 deaths per 100,000 in 2019.

Again, there are a lot of things at play here — too many to try and unpack. But having just experienced the pandemic, and the response by people of certain political affiliations to the danger it presented to their communities, I don’t find this all that surprising.

And there’s also this, which meshes with the first study I mentioned:

The results show that the gap in overall death rates between Democratic and Republican counties increased more than sixfold from 2001 to 2019, especially for white populations, and was driven mainly by deaths due to heart disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, unintentional injuries, and suicide.

Finally, while tangentially related, I wanted to bring up this recent opinion piece published in Bloomberg by Justin Fox, which argues that New York City is much safer than small-town America — this caught my eye because I’ve been saying this for years. Again, this is an opinion piece, but it’s interesting to read through. There have also been studies that back this notion up.

It’s an interesting exercise in our perception versus reality. We tend to think that we’ll be safe from violent crime or other things in a relatively small town. Big cities, obviously, have their fair share of crime, and are, as many assume, more dangerous. That’s true for some cities, and definitely in certain parts of some cities (shoutout to Scaryaki and all my boys down at 3rd and Pike!) But the stats don’t really show that to be true.

Anecdotally, I do some volunteer work with my local fire department, and as a part of our training, we were taught that people are MUCH more likely to die at a relatively young age in rural areas versus urban ones. A big part of that is that people in rural areas spend a lot more time driving, and die in auto accidents much more frequently. But there’s more to it.

Anyway, here’s a snippet from the piece:

The overall lesson seems to be that the more urban your surroundings, the less danger you face. High homicide rates in some cities mean that the central counties in large metropolitan areas are on the whole slightly more dangerous than the suburban counties, but that’s the only exception. The risk of death from truly external causes, as defined here, is three times higher in rural and small-town America than in the country’s largest city.

I spent my teenage and college years in a rural area outside of a medium-sized city. I’ve spent the majority of my adult life in two large cities: Seattle, and New York City. I can say that I’ve always felt much safer in a city, and I’ve seen first-hand how the environment can lead to these “deaths of despair.”

I’ve seen how frequent and commonplace it is, for example, for people to drive drunk in rural areas. There are guns around. I’ve seen people start bonfires with gasoline cans, and then jump an ATV over the fire. I’ve watched friends — feeling that they had no options — turn to drinking or drugs, slowly killing themselves. I’ve seen a lot of violence, which may not have been obvious to me at the time, in these areas.

Not to say these things don’t happen in cities, but again, I think it comes back to a sense of community. In a city, you’re surrounded by people all the time. You’re out and about. You’re exposed to a lot of things, whether you want to be or not. Maybe, for many people living in isolated areas or living isolated lives, the lack of community is having a large, negative effect. And those communal resources that we’re evidently in desperate need of? They’re a lot easier to find and access in certain areas.

Again, this is all a big bummer, but I feel like it’s worth bringing attention to it. Take care of yourselves and your neighbors.

Numbers, Links, and Faces

$0: What interns at the White House have been paid until this fall, when they will earn $750 per week. (NPR)

$5 million: The value of ancient artifacts destroyed at the Dallas Museum of Art by a young man who was “angry at his girl.” (Fox7Austin)

A+: Software designed to catch cheating test-takers is not working correctly and ruining students’ lives. (The New York Times)

“It’s scary.”: The U.S. is the richest country on Earth and for some reason, we can’t even feed our damn babies. (The Washington Post)

“I don’t understand why they didn’t stick to their guns.”: The Fed has been clear that there’s only so much it can do about inflation, but it seems to be losing the message. (Politico)

Frowny Face: We know how to stop school shootings, and we’ve known for 20 years. (Fivethirtyeight)

Smiley Face: The biggest plant in the world was discovered off the coast of Australia, and it covers 77 square miles and dates back 4,500 years. (BBC)